“They were careless people,” F. Scott Fitzgerald writes of the idle rich in his time. “[T]hey smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” In our time, the disconnected and wealthy radical MAGA justices of the Supreme Court have now spent weeks smashing things—from our democracy to the ability of our public health agencies to keep us safe. Now it’s up to us to clean up the mess they have made.

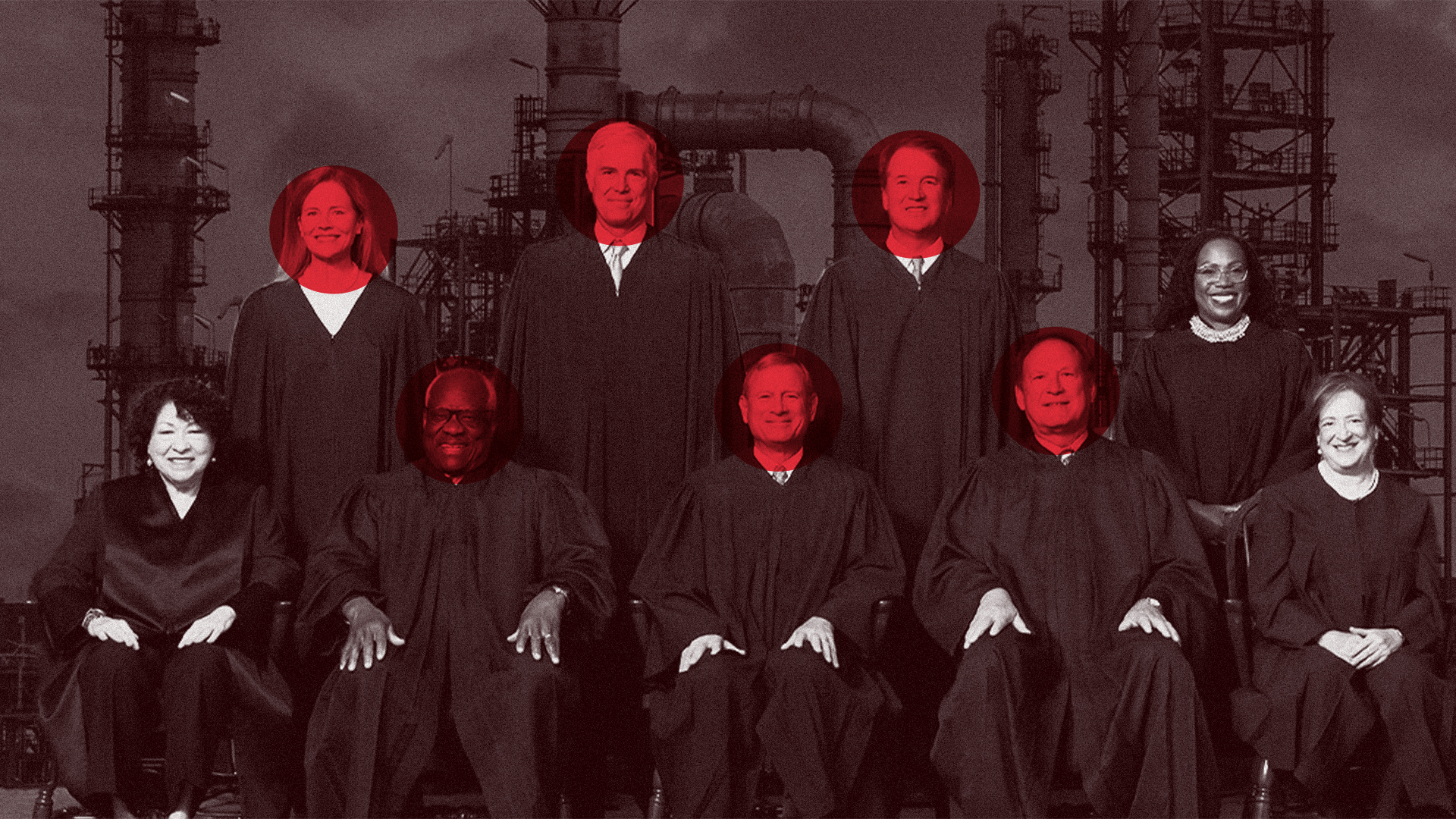

Justice Elena Kagan has called out the Trump-built majority of the Court for hubris—the pride that comes before a fall. And in their hubris, the Court’s MAGA majority has opened the door for the climate movement to go after decades of agency doctrines and loopholes designed to benefit corporate polluters. In their rush to grant Big Oil the power to dismantle the regulatory state, they failed to consider how much the existing regulatory landscape has been shaped to water down enforcement of our most important environmental laws to the benefit of the fossil fuel industry. If the Court will no longer defer to agency interpretation of these statutes, the climate movement stands ready to go after every agency interpretation that has let the industry off the hook.

The truth is that the Supreme Court has almost always ruled to protect power and against the people, from defending slavery to upholding segregation to attacking the New Deal. Each time, the hubris of the elite lawyers on the Court has been met with people power and by Congress—reining in the Court to re-establish the promise of democracy. It is time, again, to do so.

The Court and the Climate: How We Fight Back

Start with the bad news: The Supreme Court has repeatedly made up new rules, Calvinball style, to attack environmental and public health agencies, over the last few terms. Here’s what we’re facing:

- By overruling the “Chevron” doctrine, the Court has eliminated the obligation of federal judges to defer to expert agencies interpreting technical statutes, allowing right-wing judges to impose their own nonexpert and ideological views.

- While attacking EPA’s Obama-era “Clean Power Plan” for power plant carbon pollution, the Court fabricated a “major questions” doctrine (PDF) that right-wing judges read as a license to reverse agency actions by claiming agencies lack clear authority for important actions unless Congress passes a new statute. The big climate actions the Clean Air Act (CAA) actually requires EPA to take are thus open to judicial second-guessing, made worse by the Chevron overruling.

- Doubling down, the Court attacked clean water protections, and environmental protections generally, by ruling that even when clear environmental laws exist, the Court could still overrule agency actions if those actions limited states and private property owners from using their property.

- The Court has also severely limited agencies’ ability to enforce basic laws against bad actors without going through costly jury trials and has made it easier to challenge agency actions even years after the fact.

With the basics of administrative law being scrambled to serve MAGA goals, all may seem lost. Fortunately, the Court rulings are not the unmitigated victories for fossil fuel interests that they seem to be, as every one of these decisions can be reversed or limited by a new statute via Congress.

Here’s why. The Court keeps insisting that agency actions must closely follow clear statutes passed by Congress. It seems eager to return to those laws. But let’s remember, those laws are not on the Court’s side. They were passed by Congresses that were deeply concerned with protecting the public, and if we take them seriously and apply them clearly, the outcome should not be what the Big Oil wants.

If Courts Want to Follow the Laws Literally, Let’s Use Their Logic to Our Advantage

Look at it this way. The big federal environmental laws have made sweeping changes to the federal agencies, and the Supreme Court just said that it is time to take their language seriously. First, take the Clean Water Act. It bans water pollution entirely unless EPA issues a permit and tells EPA the goal is to eliminate water pollution (PDF) by 1985. That’s not how agencies have implemented it, but it's clear text requires more. Second, the National Environmental Policy Act (PDF) orders that the entire federal government “fulfill the responsibilities of each generation as trustee of the environment for succeeding generations.”

Sure, the agencies and the courts have instead treated this command as unenforceable, but that is not what the law actually says. The Clean Air Act repeatedly orders the use of the “best” approach to control pollution at every major pollution source. Agencies have imported all sorts of limits on that command to serve industry, but the statute is clear: Best means best and should bar fossil fuels in many sources now that zero-emission technology is available. The list goes on and on.

Put another way, since the big environmental statutes have been written, federal agencies have often been under the control of right-wing appointees who have ignored what Congress actually wanted. There are decades of agency doctrines, decisions, and guidance documents from those eras. If the Supreme Court now wants courts to stop deferring to what those corporate appointees wanted, fair enough. But that outcome does not necessarily put fossil fuel interests in charge. It takes us back to the clear text of visionary laws that the environmental movement fought for and enacted, from the Clean Air Act to the Inflation Reduction Act. If we take the Court at their word, then let’s seriously implement those laws.

How We Can Use End of Chevron to Close Pollution Loopholes

In fact, let’s start with Chevron itself. That doctrine emerged from a pro-fossil fuel decision made by Neil Gorsuch’s mother, who was Ronald Reagan’s de-regulatory appointee to run the EPA. Her team decided that even though the Clean Air Act requires permits applying the best controls for each increased pollution source, oil refineries, with their legions of pipes pouring out pollution, could avoid that requirement by calculating the net pollution decreases at one pipe against the increases at another. That ruling was a gift to the Chevron corporation and has made it harder to control air pollution ever since. It’s dead now. Why should oil companies get to keep polluting if the actual text of the Clean Air Act does not allow it?

And it’s not just refineries. As Evergreen has pointed out, the air permits that regulate every big industrial facility and power plant have been issued under decades of old guidance documents, rooted in Chevron deference, that systematically undermine the switch to zero-emission technologies. Agency heads appointed by Reagan, both Bushes, and Trump made it so. But there is no reason to defer to them anymore. For example, the agency has said that requiring sources to switch to clean electricity rather than fossil fuels “redefines the source” and isn’t required. But it made that doctrine up. The actual Clean Air Act says the “best” controls are required, including switches to “clean fuels,” and electricity is a fuel, as are cleaner alternatives than coal and fossil gas. Why should that decision persist if we take the CAA seriously?

Examples abound. Trump’s EPA tried to exempt major sources of toxic pollution from the Clean Air Act via agency interpretation, risking communities nationwide, but the CAA does not say that those sources can ever be exempted. Why should the agency be able to shield toxic sources from pollution reductions?

Or take another example: The Clean Air Act requires that EPA ensure that sources monitor to make sure they are not polluting communities, but EPA has limited monitoring requirements over the years. Perhaps it is time to return to the CAA’s actual, rigorous requirements.

Or look at vehicle pollution. The actual text of the CAA requires EPA to set standards for each class of vehicle engines, but for years EPA has allowed car companies to average different kinds of engines against each other based on vehicle size. That’s why SUVs can offset massive pollution against smaller zero-emission vehicles. Perhaps it’s time to stop allowing giant oil-hog vehicles to average out their harms, if we take statutory text seriously. There are seemingly endless examples like these, and now, decades upon decades of agency decisions to weaken or bend environmental laws to make them easier for industry stand open to challenge.